Table of Contents

Yesterday, I got into a verbal altercation at Starbucks.

An older man, talking very loudly, said something along the lines of “My son is golden because he has a degree from Stanford University.”

This comment really infuriated me because this type of outdated thinking—that a college degree from an elite, pricey university means you’re set for life—must die immediately. It falsely signals to employers that you’re better than the average Jane just because you have a piece of paper. In reality, all it really signals is your family’s socioeconomic status.

So I interjected and said, “Let me guess… You paid for your son’s education.”

“I did,” he said. “My son’s grandfather was Herbert Hoover, and my son’s degree is like gold.”

[Eye roll]

I preceded to tell him that it doesn’t matter if you have a college degree anymore to do today’s jobs and that he was basically bragging about his family’s socioeconomic status, not his son’s actual achievements. I tried to elaborate about the inequalities of higher education and why it’s an outdated metric of future success. I explained why employers are absolutely wrong for thinking his son is better than someone without a degree or a degree from a public university.

Then he told me to go fly a kite, because that’s usually what happens when people are wrong and have zero evidence that their stance is right and yours is wrong. (I’m always open to new ideas, SO LONG AS you present trustworthy facts, stats, and research.)

For the record, this man is an out-of-touch elitist, and I stand by everything I said to him.

Fun fact: The median family income of a student from Stanford is $167,500, and 66% come from the top 20%. About 2.2% of students who attended Stanford came from a poor family but became a rich adult.

The sad truth: money drives admission

Stanford is far from an anomaly, according to New York Times.

At 38 colleges (at least) in America, including five Ivy League schools—Dartmouth, Princeton, Yale, Penn, and Brown—more students came from the top 1% of the income scale than from the entire bottom 60%.

According to an in-depth New York Times analysis:

Roughly one in four of the richest students attend an elite college—universities that typically cluster toward the top of annual rankings (you can find more on our definition of “elite” at the bottom).

In contrast, less than one-half of 1% of children from the bottom fifth of American families attend an elite college; less than half attend any college at all.

Degrees impact employment and lifelong earnings

Yet, nine out of 10 new jobs created in 2018 went to those with a college degree.

College graduates earned 80% more per week than high school graduates, with The Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting that Americans with a bachelor’s degree have median weekly earnings of $1,173, compared to $712 for those with only a high school diploma.

And according to the United States Social Security Administration, men with bachelor’s degrees earn around $900,000 more over the course of their lifetime than high school graduates, while women with bachelor’s degrees earn $630,000 more.

Degree requirements lead to less diversity

Recruiters use software, known as Applicant Tracking Systems (ATS), which I discuss in detail in a previous article. ATS collect, sort, and filter job applicants who apply through an online form.

They use this tool because the average job post receives 250 applications today, and they need a way to save time filtering down candidates.

Sometimes, online application forms will feature “knockout questions,” like “Where did you graduate from?” “What year did you graduate?” and “What did you major in?” These are meant to automatically weed out candidates who don’t meet certain criteria.

For instance, if I—a college dropout—were to apply to a job with these knockout questions, I’d automatically be filtered to the rejection pile, with not one human actually taking the time to even scan my resume. All because I don’t have a Bachelor’s degree, despite my 10 years of professional, proven experience.

Even if application forms don’t feature knockout questions, recruiters are likely inputting “keywords” into their ATS, searching for words like, “Bachelor’s,” “Harvard,” etc., just to quickly filter down the amount of resumes they have to review.

Let me be clear: Filtering candidates by degree is the epitome of wrong and legally, it’s actually discriminatory, which could be a massive liability for companies requiring a Bachelor’s degree or higher to even be considered for employment.

This sounds like crazy fake news, but according to an article on the reputable legal encyclopedia, NOLO, I’m right.

In the post, a reader asks if requiring a college degree for employment is illegal:

I work for a large nonprofit employer whose mission is to help inner-city children finish high school and go on to college.

We do fundraising, provide tutors and coaches, work with teachers and parents, and help school districts come up with strategies and resources to reduce dropout rates, among many other things. Our employees do everything from sending out mailings and answering phones to lobbying Congress to helping kids with their math homework and college applications.*

Recently, the Board decided to require all new employees to have a college degree. The Board feels that it would be great for the kids and their families we work with to see the benefits of staying in school; the Board has also said that having employees who never finished high school or college runs counter to the message we’re trying to send about the importance of education.

I can see their point, but I’m concerned that this requirement might screen out large numbers of applicants of color. Is it legal for us to adopt this hiring requirement?*

*Side-note: Why are so many entities STILL preaching college as the only way to get a job and succeed in life, when 50% of grads are underemployed or unemployed today? See chart below.

NOLO’s answer:

Whether or not a hiring requirement is discriminatory depends on its intent and its effect. Some employers adopt screening tests or criteria with the purpose of screening out certain applicants. For example, imposing a strength test would have the effect of screening out larger numbers of women. If an employer’s intent is to discriminate, and its hiring criteria are simply a smokescreen for this true purpose, then the employer is discriminating. But even if an employer has no intent to discriminate, its hiring criteria may have that effect. If a selection test or requirement has a disproportionate effect on applicants in a particular protected category, that might be illegal discrimination. The key is whether the requirement is truly necessary to do the job. For example, a strength test might screen out disproportionate numbers of female applicants, but might also be necessary for a job as a firefighter, construction worker, or logger.

An employer whose screening test or requirement has a disparate impact on a protected group must show that the requirement is job-related and consistent with business necessity. This is intended to be a difficult hurdle, but not an impossible one. For example, an attorney needs to pass the bar exam to practice law, so requiring applicants for an associate position at a law firm to be admitted to the bar would meet this test. Similarly, many skills tests would pass legal muster, as long as the exam tested skills that truly were necessary to do the job.

Degree requirements are more slippery, in part because it isn’t clear exactly what particular skills, aptitudes, or abilities a degree confers (unless a particular degree is required for licensing, like a law degree or medical degree generally is). And, degree requirements often do have a disparate impact against African American and Latino applicants.

…

Your Board has expressed a nondiscriminatory reason for its new requirement. But a court would look at whether it really is necessary to have a college degree to do every job at your company. The variety of jobs employees hold is going to be a major strike against the requirement: It seems pretty evident that someone can stuff envelopes, answer phones, manage databases, and do a wide variety of other work without a college degree.

And, even if a court were to accept the employer’s “role model” argument for certain positions, an applicant could still win a discrimination lawsuit by showing that there are less discriminatory alternatives available. For example, an employee might be an even more effective advocate for staying in school if he or she can share how difficult it has been to succeed without a degree. An employee who has dropped out might be better able to relate to the decisions facing at-risk kids and better able to help them make a different choice. In short, if a degree requirement has the effect of screening out larger numbers of African American and Latino applicants, your employer will face a very difficult task in trying to justify the disparity.

That last sentence is key. Today, the hot topic in HR today is “diversity.” Diversity for women, for latinos, for African-Americans, etc. But these are actually vanity metrics at best (or total lies at worst) if the company requires a college degree for employment—whether or not they realize it.

Degree requirements actually lead to less diversity.

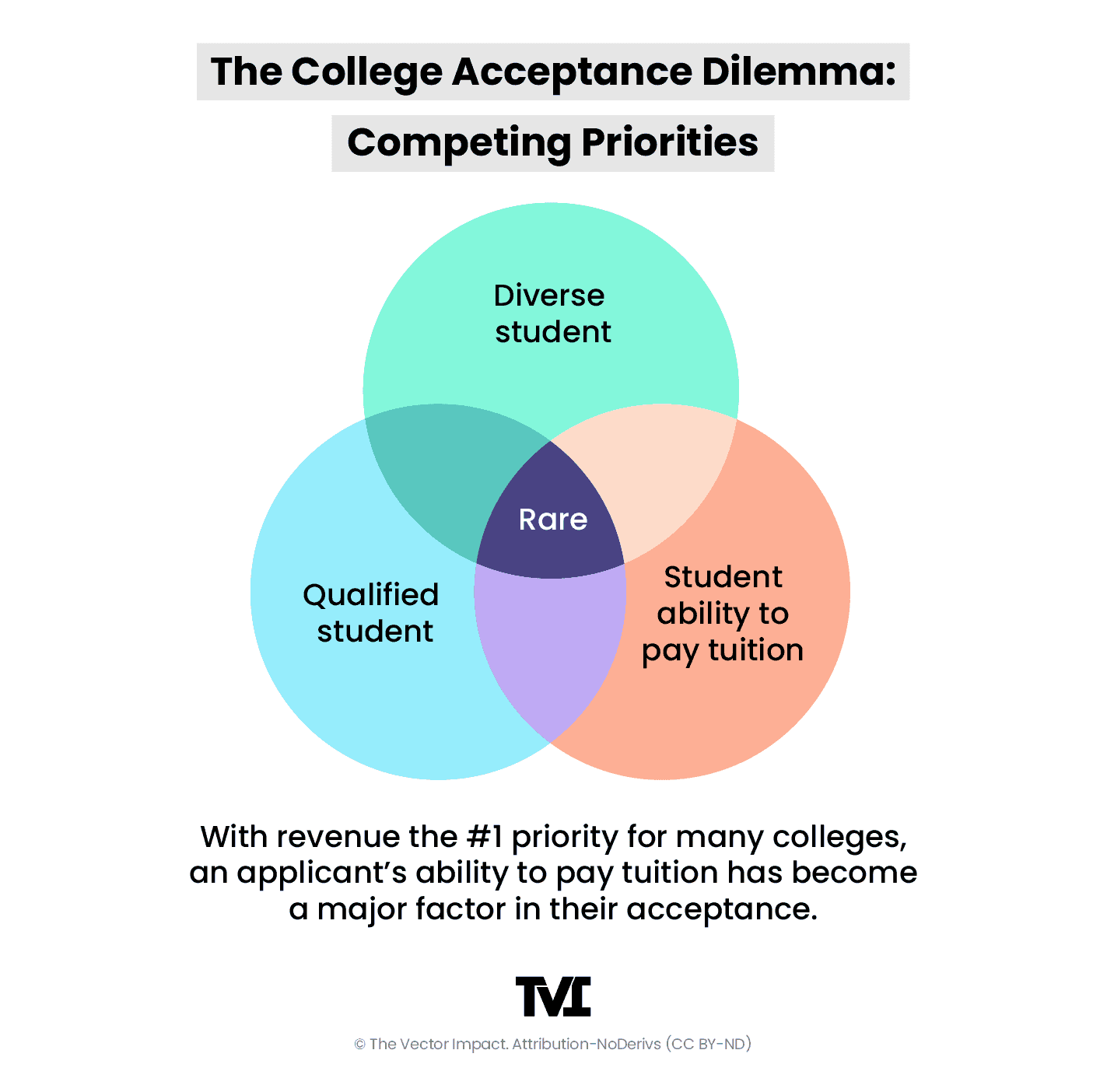

The strongest predictor of entrance and completion of a degree at a top-tier university isn’t merit, but family ability to pay.

So all your degree requirement really says to candidates is, “I discriminate based on your parents’ socioeconomic status.”

The higher education industry has been very publicly proven to be a complete pay-to-play farce.

Case in point No. 1: Rich people pay to get their kids into college

At least 53 people, including actresses Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman, as well as executives at prominent companies, venture-capital firms, and law offices, have been charged with participating in the college admissions scandal, a scheme involving bribery, money laundering, and document fabrication to unfairly get students admitted to elite colleges. In total, these powerful parents shoveled out more than $25 million between 2011 and 2018 to ensure their kids would get into certain universities.

The thing that kills me is their kids didn’t even want to go to school, and if they got in, they probably would’ve paid people to take their classes and do their assignments for them, as A LOT of rich kids do to make it to graduation. (Trust me, I have a lot of rich friends.)

Here’s more links on the topic, in case you haven’t already read about it.

- Here’s the Full List of People Charged in the College Admissions Cheating Scandal, and Who has Pleaded Guilty So Far

- How I Would Cover the College-Admissions Scandal as a Foreign Correspondent

- Here’s the Latest on the College Admissions Scandal

- College Admissions Scandal category on New York Times

Case in point No. 2: Colleges don’t even admit the best applicants

According to two in-depth investigations conducted by New York Times and Washington Post, colleges are not in fact admitting the best, most worthy students. They’re accepting the kids whose family can afford to pay tuition, because let’s remember, folks, higher education is an industry, which means they want to make the most revenue possible, just like all corporations do.

You should definitely read the two articles (here and here), but I’ll give you a brief overview of today’s jaw-dropping college admissions’ process.

If you didn’t already hear the news, colleges are struggling hard core to generate enough revenue to survive. In fact, about a quarter of private American colleges are now operating at a deficit, spending more than they are taking in, which means revenue is priority No. 1, but it comes at the cost of accepting the best, most diverse group of students.

To the public, college boards and admissions offices say that they’re not accepting amazing but poor students, not because they don’t want to, but because the kids from lower socioeconomic backgrounds don’t apply in the first place.

Over the last decade, two distinct conversations about college admissions and class have been taking place in the U.S. The first one has been conducted in public, at College Board summits and White House conferences and meetings of philanthropists and nonprofit leaders. The premise of this conversation is that inequity in higher education is mostly a demand-side problem: Poor kids are making regrettable miscalculations as they apply to college. Selective colleges would love to admit more low-income students—if only they could find enough highly qualified ones who could meet their academic standards.

Behind closed admissions’ doors though, that’s just not the case.

The second conversation is the one that has been going on among the professionals who labor behind the scenes in admissions offices—or “enrollment management” offices, as they are now more commonly known. This conversation, held more often in private, starts from the premise that the biggest barriers to opportunity for low-income students in higher education are on the supply side—in the universities themselves, and specifically in the admissions office. Enrollment managers know there is no shortage of deserving low-income students applying to good colleges. They know this because they regularly reject them—not because they don’t want to admit these students, but because they can’t afford to.

Only a tiny minority of American colleges, like Harvard, Princeton, and Stanford, don’t worry about tuition revenue because they have such ginormous endowments and reliable alumni donors that they can give its students more without charging more.

The overwhelming majority of private colleges make all, or most, of their money on tuition and room-and-board. I’ll illustrate what this plays out like at Trinity college.

When Trinity’s current admissions officer was hired, he was extremely concerned.

We were taking some students who probably should not have been admitted, but we were taking them because they could pay. They went to good high schools, but they were maybe at the bottom of their class. The motivation wasn’t there. So the academic quality of our student body was dropping.

Basically, the director’s predecessors capitalized on a pattern that admissions officers say they often see:

The students who get admitted are usually the ones from expensive prep schools, at the bottom of their class, but above-average SAT scores, because they have access to proven test-prep classes and tutors (or have a parent like Lori Loughlin who pays a smart kid to take it for you). These students aren’t motivated. They’re doing the bare minimum in high school. But they’re getting into college despite the fact they didn’t work as hard as their peers, all because they learned how to game the SAT or ACT.

For many colleges, good SAT scores make them feel better about the kids they’re admitting each year just because they can pay full tuition.

It’s hard to feel good about choosing an academically undeserving rich kid over a striving and ambitious poor kid with better high school grades. But if the rich student you’re admitting has a higher SAT score than the poor student you’re rejecting, you can tell yourself that your decision was based on ‘college readiness’ rather than ability to pay.

The problem is, rich kids who aren’t motivated to work hard and get good grades in high school often aren’t college-ready, however inflated their SAT scores may be.

The colleges with high average SAT scores—which are also the highest-ranked colleges and the ones with the lowest acceptance rates and the largest endowments—admit very few low-income students and very few black and Latino students. In fact, the below chart shows an almost perfect correlation between institutional selectivity and students’ average family income, a steady, unwavering diagonal line slicing through the graph. With only a few exceptions, every American college follows the same pattern.

If you’re an enrollment manager, the easiest category of students for you to admit are below-average students from high-income families. Because their parents can afford tutoring, they are very likely to have decent test scores, which means they won’t hurt your U.S. News ranking. They probably won’t distinguish themselves academically at your college, but they can pay full tuition. And they don’t have a lot of other options, so they’re likely to say yes to your admission offer. These are the kids who will gladly pay more to move up the food chain. I call them C.F.O. Specials, because they appeal to the college’s chief financial officer. They are challenging for the faculty, but they bring in a lot of revenue.

But wait, here’s the real kicker.

As I mentioned, some of the most selective colleges have so much money that they could easily admit freshman classes made up entirely of academically excellent Pell-eligible students and charge them nothing at all. The cost in lost tuition would amount to a rounding error in their annual budgets.

But not only do those and other selective colleges not take that step; they generally do the opposite, year after year. As a group, they admit fewer Pell-eligible students than almost any other institutions.

Colleges like DePaul, with much smaller endowments, somehow manage to find the money to admit and give aid to twice as many low-income students, proportionally, as elite colleges do.

Why don’t the most selective colleges do more? The answer: Staying “elite” depends not just on admitting a lot of high-scoring students. It also depends on admitting a lot of rich ones. In fact, researchers Nicholas A. Bowman and Michael N. Bastedo showed in a 2008 paper that when colleges take steps to become more racially or socioeconomically diverse, applications tend to go down in future years. “Maybe— just maybe—the term ‘elite’ means ‘uncluttered by poor people,’. And maybe that’s the problem?

Case in point No. 3: Colleges admit the applicants who can pay

According to the Washington Post article, while colleges have been using data for many years to decide which regions and high schools to target their recruiting, the latest tools let administrators build rich profiles on individual students and quickly determine whether they have enough family income to help the school meet revenue goals.

An admission dean is more and more a businessperson charged with bringing in revenue,” Thacker said. “The more fearful they are about survival, the more willing they are to embrace new strategies.

While tracking software, like Google Analytics, has been around forever now, many U.S. colleges have just started installing it on its websites, but the way they’re using the data to make decisions about who gets into their school is a big hairy ethical issue.

Take the University of Wisconsin-Stout, which installed tracking software on its site:

When one student visited the site last year, the software automatically recognized who she was based on a piece of code, called a cookie, which it had placed on her computer during a prior visit. The software sent an alert to the school’s assistant director of admissions containing the student’s name, contact information and details about her life and activities on the site. The email said she was a graduating high school senior in Little Chute, Wis., of Mexican descent who had applied to UW-Stout. The admissions officer also received a link to a private profile of the student, listing all 27 pages she had viewed on the school’s website and how long she spent on each one. A map on this page showed her geographical location, and an “affinity index” estimated her level of interest in attending the school. Her score of 91 out of 100 predicted she was highly likely to accept an admission offer from UW-Stout.

At least 44 public and private U.S. colleges are collecting more data on prospective students in order to make better predictions about which students are the most likely to apply, accept an offer, and enroll.

Records and interviews show that colleges are building vast repositories of data on prospective students—scanning test scores, Zip codes, high school transcripts, academic interests, Web browsing histories, ethnic backgrounds and household incomes for clues about which students would make the best candidates for admission. At many schools, this data is used to give students a score from 1 to 100, which determines how much attention colleges pay them in the recruiting process.

So let’s say a prospective student visited the “financial aid” page 10 times. Her “score” is going to decrease, because she likely can’t afford to pay full tuition. Another example is an out-of-state applicant versus an in-state applicant. The out-of-state applicant is going to receive a higher score because she’s worth more money to the university. Even worse, students have no idea colleges are doing this, and if they want to not be tracked, they must contact the university directly.

Point-blank: This is 1000% unethical and unjust because as I detailed above, nine out of 10 jobs are going to those with a college degree, and more and more jobs that shouldn’t require a college degree do now.

Something must change. Colleges need to drop these discriminatory practices, or companies need to stop requiring degrees, because as of right now, who gets into and completes college and therefore lands a good job is all dependent on how much money you have. That is NOT the American dream.

Degrees are a poor indicator of on-the-job success

Maybe you’re not an ethical and empathetic person though, and you still believe in filtering applicants by college degree. Again, I’ll have to ask you why, in a world where the majority of employers claim that colleges aren’t even preparing students for the world of work.

In 2014, 96% of chief academic officers at higher-education institutions said their school is very or somewhat effective at preparing students for the world of work. While only 33% of business leaders agreed with the statement that “higher-education institutions in this country are graduating students with the skills and competencies that my business needs.” More than a third disagreed, with 17% saying they strongly disagreed.

According to another study, nearly three in four employers say they have a hard time finding graduates with the soft skills their companies need.

In 2019, the Society for Human Resource Management found that 51% of its members said that education systems have done little or nothing to help address the skills shortage.

It’s really not that surprising that companies are unimpressed with college grads, when you look at all the information I just presented to you. Wealthy kids—not all, but many—who don’t deserve to be in college in the first place because they’re lazy and game the system, graduate more than the kids who deserve to because of their family’s socioeconomic status.

Across the board the strongest predictor of entrance and completion of a degree at a top-tier university isn’t merit, but family ability to pay.

That advantage starts early, with access to strong primary education and stable parents who can help with homework. It extends into high school with access to college advisors, test prep, essay coaching, extracurricular experiences, mentorship, and financial aid. And then into college itself, with the financial ability to fund $120,000-$200,000 over four years through cash or debt, and the stability to worry about studies, not money.

In short, graduating from a university is often a sign of family status, not personal achievement. Bachelor’s degree attainment is more than 5x higher among kids from higher-income households than lower-income households.

So when you require a college degree for your open role, what you’re really saying is, “I discriminate based on your parents’ social class.”

Another reason degrees are a poor indicator of who will be a successful employee is the fact that colleges aren’t even teaching the most in-demand skills. Internal bureaucracy doesn’t allow them to make the curriculum fast enough and even if they did, it’s not agile enough to change on the fly, as needed with the pace of technology today.

A 2016 World Economic Forum report found that “in many industries and countries, the most in-demand occupations or specialties did not exist 10 or even five years ago, and the pace of change is set to accelerate.”

And recent data from Upwork confirms that acceleration. Its latest Upwork Quarterly Skills Index, released in July, found that “70% of the fastest-growing skills are new to the index.”

Expect the change to keep coming. WEF cites one estimate finding that 65% of children entering primary school will end up in jobs that don’t yet exist.

The CEO of Upwork is spot on when she says the future of work will be about SKILLS, not degrees. No one school will ever be able to insulate us from the unpredictability of technological progression and disruption.

As a leader of a technology company and former head of engineering, she hired many programmers during her career. And what matters to her “is not whether someone has a computer science degree but how well they can think and how well they can code. In fact, among the top 20 fastest-growing skills on Upwork’s latest Skills Index, none require a degree.”

Too often, degrees are still thought of as lifelong stamps of professional competency. They tend to create a false sense of security, perpetuating the illusion that work—and the knowledge it requires—is static. It’s not.

Wake up, employers! You’re spending an obscene amount on hiring, and it’s NOT working. It’s time for change.

According to Gallup, companies fail to choose the candidate with the right talent for management positions 82%of the time. That means organizations hire the best managers fewer than two out of 10 times. Another survey commissioned by Glassdoor reported that 95% of employers surveyed admitted to making hiring mistakes by recruiting the wrong people every year. And HBR found that as much as 80% of employee turnover stems from bad hiring decisions.

Additionally, only about a third of U.S. companies report monitoring whether its hiring practices actually lead to good employees; few do so carefully, and only a minority track cost-per-hire and time-to-hire.

Employers spend a ginormous amount on hiring—an average of $4,129 per job in the U.S.—and many times more than that for managerial positions—and the U.S. fills a staggering 66 million jobs per year. Most of the $20 billion that companies spend on human resources vendors goes to hiring, which begs the question: Why do employers spend so much on something so important while knowing so little about whether it works?

If I haven’t convinced you to drop your degree requirements, fine, but at the very least I challenge you to at least start tracking where the best employees come from and how long they stay with the company and why they leave, etc. This will not only show you how to find better employees, who stay longer, but it will also shield you of the risk of a discrimination lawsuit and tarnished brand reputation.

And here’s some food for thought before you go: Maybe if you actually invested in someone with potential and proof they’d succeed in a given role, they’d be loyal to you for life. Give before you take.

That’s how you win allies and employees for life.